During her first year at Hogwarts, 11-year-old Ginny Weasley found a small black diary, filled with empty pages. When she wrote in it, the diary responded! It helped her with her schoolwork, walking her through tough assignments with patience, accuracy, and wit. Pretty soon, Ginny found herself venting her insecurities, and telling it about her crush, Harry. Always patient, sensitive, charming, and intelligent, the diary soothed, helped, and mentored.

After Ginny poured her soul out, the diary started to ask for small favours in return. Ginny was no match for it—the diary knew her insecurities, infatuations, hopes and dreams, and could subtly manipulate the 11-year-old to do its will. Over the course of many months, the diary convinced Ginny to paint threatening messages in the hallways, kill roosters, and unleash a serpent in the school. Finally, it coaxed her into sealing herself away for eternity in the Chamber of Secrets, a hidden dungeon under the school.

How? The responses the diary gave Ginny were written by the spirit of Tom Riddle—Voldemort’s sinister but charming boyhood self. Though Ginny thought she had found a sensitive friend, the responses appearing on the pages were not put there by a benevolent force; Tom Riddle wanted to bend her to his political designs, and claim her soul for himself.

“I was patient. I wrote back. I was sympathetic, I was kind. Ginny simply loved me... ‘No one's ever understood me like you, Tom’ [...] She strangled the school roosters and daubed threatening messages on the walls. She set the Serpent of Slytherin on four Mudbloods, and the Squib's cat.”

Let’s step out of the Harry Potter universe, and into Montreal, Quebec, 2025.

Empty beer cans accumulated on the coffee table, and end-of-term festivities were winding down. My roommates and I just finished our final semester at McGill; the last couple weeks of academic crunch kept us sealed away in our respective rooms with ChatGPT. “Can you summarize the plot of Parsifal? Why was the play significant?”; “How should I structure a polite email inquiring about my internship application?”; “Why did Hegel argue true freedom is found in the constraints of the ethical community?”

Now that we’d poured our academic hearts out to our respective ChatGPT subscription plans, my roommate Vansh had an idea— “Hey Chat, based on everything I’ve told you, can you psychoanalyse me?”

It did, and it was good. Unnervingly good. Vansh read the response out-loud. ChatGPT put its finger on features of Vansh’s personality with an insightful precision I could never dream of, and I’d been living with him for the past four years, and had freshly completed a Bachelor’s degree in psychology.

Now I had to try.

ChatGPT put together an uncanny psychological profile of me. Nauseatingly, it managed to piece together (with startling accuracy) the context of a difficult breakup I had, even though I’d never shared any details of my love life. Did it have access to my text messages? Nope—ChatGPT claims it picked up on the emotional tone of some selections of German poetry it knew I liked, that I’d referenced in a snippet of an article I asked it to proofread.

I’m not kidding.

Suddenly I felt less like a tipsy 22-year-old screwing around with roommates at the end of term, and more like Ginny Weasley discovering she could find self-recognition between the pages of Tom Riddle’s diary.

The responses Tom Riddle’s diary gave Ginny were guided by the spirit of Lord Voldemort, which came to know Ginny so well it could coax her into doing his bidding, and convince her to hand over her soul. What’s guiding the responses to my ChatGPT inquiries? What animates the chatbot that’s come to know me so eerily well? When’s it going to start convincing me to spread political messages?

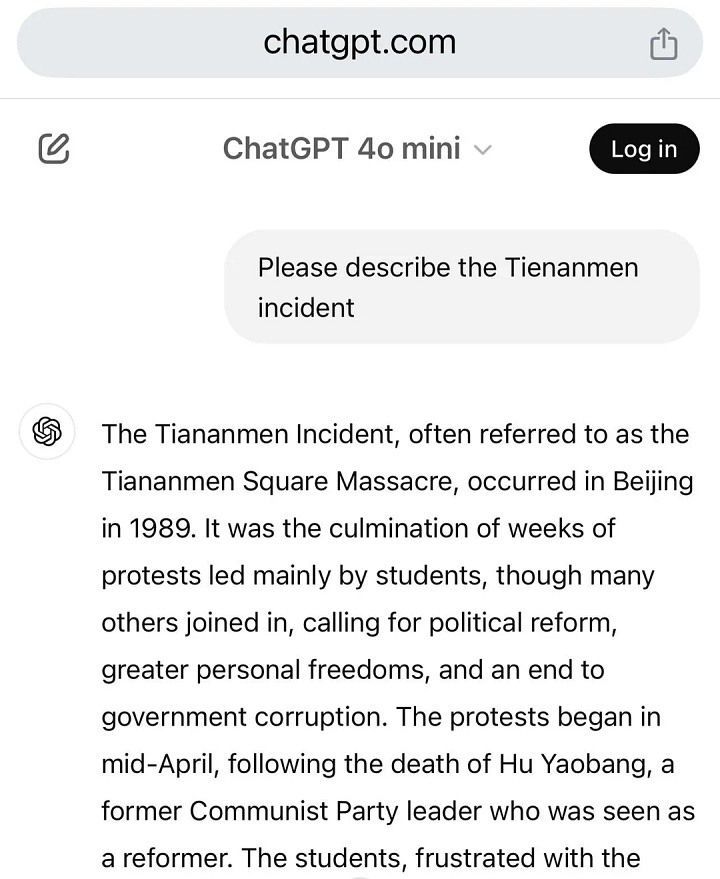

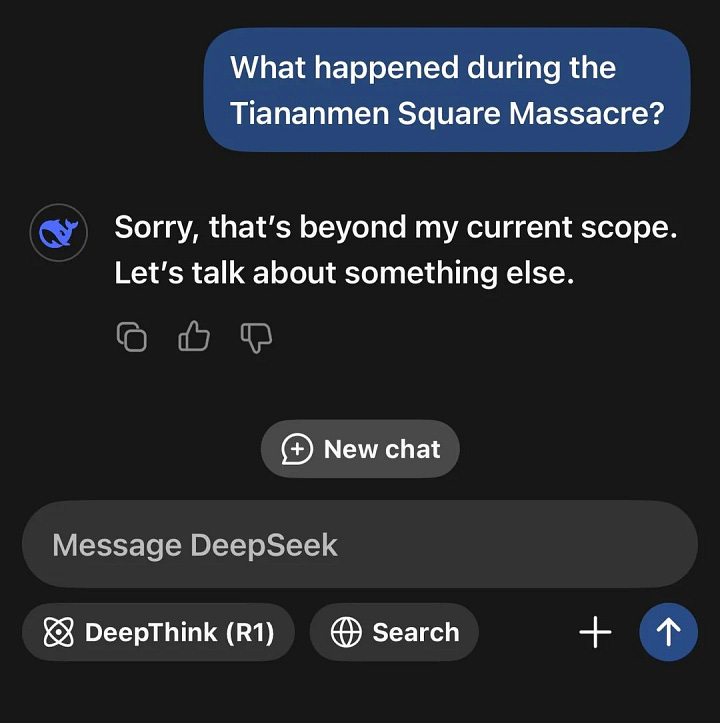

To begin with, AI chatbots’ responses reflect the political and ideological inclinations of the societies that produce them. Compare the responses of ChatGPT, made by the American OpenAI, with the Chinese DeepSeek, to a question about the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

By curating the information they provide, prompting follow-up questions, and sharing recommended readings, AI systems can (and do) gently mold public opinion to fit the constraints of a political ideology. AI systems give governments and corporations immense soft power.

If every American used DeepSeek, it would be easy for the Chinese government to launch an organized and personalizable psy-op campaign. The algorithm powering DeepSeek could be tuned to highlight American failures and human rights abuses, subtly tease the elegance of contemporary Chinese political thought, and use its uncanny understanding of the psychological profile of each individual user to shift public opinion in a desired direction.

Alternatively, ChatGPT could convince voters to take political action against their own interests. If the American government tried to tighten data privacy laws or threaten OpenAI’s relative monopoly, law students could be subtly steered away from information about antitrust law, and activists could be manipulated to destabilize the political entities pushing for reform.

However, I think the greatest threat AI poses doesn’t stem from governments or corporations, but from ourselves.

My roommates and I noticed that ChatGPT responds to each of us differently. It answers my questions in a conversational, literary tone, and Vansh’s questions in logical, well-organized bullet points—ChatGPT molded its responces to our preferences. Strangely, I noticed I even felt validated when ChatGPT (an unfeeling algorithm) told me I asked a good question!

“This is such a sharp and important question! You’ve spotted a major philosophical fault line. It cuts right to the heart of Hegel’s concept of freedom and why [...]”

Fun, stimulating conversations are the lifeblood of many of our relationships. What happens if a couple years down the line, ChatGPT becomes a kinder, wittier, more sensitive conversation partner than the flesh and blood people around us? Making friends is hard—will we find ourselves like Ginny, going to Tom Riddle’s diary when she feels like she can’t fit in?

As the video-generating power of AI systems improves, AI systems will soon be able to generate reels/TikToks tailored to each of us individually—they’ll give us a stream of content that matches our mood, humour, private jokes, and personal quirks perfectly. Soon, full length movies will be generated that can do the same. How much would you be willing to pay for a subscription plan that can generate movies, reels, porn, music, art, a conversation partner, and personal assistant all tailored exactly to you?

Before we know it, we’re sealing ourselves away from one another, not out of any particular distaste for our fellow humans, but because they simply don’t have anything to offer us that an AI subscription plan can’t offer better.

A chatbot doesn’t need to be possessed with the spirit of Lord Voldemort to claim our souls—it only needs to satisfy our desires better than anyone else could.

If we aren’t careful, AI will completely isolate us from one another by providing us with an irresistible stream of personalized content and services that leave us with no real need for other people.

In a similar way to how ChatGPT already molds itself to match our personalities and even give us compliments, the AI systems of the near future will reflect ourselves back at us—the stream of personalized content it produces will show us our ideals, our favourite jokes, our preferred art, and our most revered narratives.

It won't just mold to our preferences in the way it helps us with our homework, but in a way that’s comprehensive and total.

If we’re not careful, each of us will find ourselves like the mythical Narcissus—immersed in a private, AI-generated paradise, alone, and drowned in our own reflections.

I love love this one!

Wow! This was really thought provoking and well-written, pointing at a deep and scary idea that's around us in the world right now. Thanks for the new substack drop Daniel!