GUEST ESSAY: Dancing on the Nib of the Pen

Seventy Years of Gaokao Essays, One Relentless Narrative—Humanities Education in China

This is a guest essay by the incredibly talented Dylan Chang. Dylan is a second-year Philosophy and Statistics student at McGill University. He grew up in Wuhan, China, and is interested in political philosophy, memory, and the intersection of personal narrative, and public truth.

“If I were a bird,

I too would sing with a rasping throat.”— Ai Qing, “I Love This Land”

This weekend marks the arrival of China’s 2025 college entrance exam season. An estimated 13 million students will sit for the Gaokao—the gruelling test that has, for most of them, functioned as a pre-existing fault line in their lives long before they could even write their names. The exam unfolds in the thick, damp pressure of the East Asian monsoon season—a fitting backdrop for an event that, for many, decides the arc of their adult lives.

In most Chinese provinces, students are divided into two tracks —wenke (liberal arts) and like (sciences). Liberal-arts candidates sit six tests (Chinese, liberal-arts-math, English, politics, history, geography), while science candidates take Chinese, science-math, English, physics, chemistry, and biology.

Though there is some regional variation in the structure of the Gaokao, one constant binds every province and every track: Chinese remains compulsory for all. Whether a student hopes to be an agricultural technician or a frontline journalist, they must produce an exceptional essay on Chinese literature. As the only humanities course every student in the country has studied in lockstep since the age of six, the exam measures far more than a student’s command of grammar and prose. Chinese is the barometer of the state’s cultural and ideological policy, the vessel through which national identity is encoded, rehearsed, and assessed.

Each year’s Gaokao essay topic sends a carefully engineered signal—not just to students and teachers, but to parents, media, and international observers alike: what kind of citizen does the Chinese state wish to produce this year?

Since the Gaokao was born in 1952, its essay prompt for the Chinese literature exam has inhaled and exhaled politics with metronomic precision, tracing the changing melody of Chinese political ideology.

In the 1950s, fully-prescribed essays like “In the Bountiful Rice Fields” extolled “new people, new deeds”, celebrating socialist construction. The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) erased the exam entirely, leaving a ten-year void. When Gaokao returned in 1977, one signature prompt—“My Year of Revolutionary Struggle”—asked candidates to write a hymn to the Party’s triumph over the Gang of Four.

Deng Xiaoping’s 1980s reforms nudged the educational focus toward cartoons and source-material prompts, gauging social observation more than class struggle. In 1994, the first open-topic essay, “Me, Twenty Years from Now”, let examinees choose genre and angle independently, cracking the door for personal voice. The 2000s pivoted to half-finished prompts on integrity and resilience, in tune with newly emerging ideals of harmonious society and scientific development.

From 2015 on, Gaokao reform allowed more regions to adopt task-based writing—proposals, speeches, public letters—drilling civic duty and the importance of mass communication. The 2020s added a “micro-essay + long essay” format; one 2024 prompt, “Exploring the Far Side of the Moon,” fused cosmic curiosity with tech nationalism. Over six decades, the Gaokao essay has drifted from collective anthem to a science-and-humanities hybrid, mirroring the Party’s talent ideal as it inches—gingerly—from obedience and organization toward analysis and innovation.

Despite all the talk of “reform,” Gaokao prompts have never dared to lay a finger on China’s still-unhealed wounds.

No prompt asks students to reckon with the Great Leap famine, the violence of the Cultural Revolution, or the bloodshed of 1989; the deepest wounds of one-party rule remain officially untouched. When writers of the early 1980s began to cautiously engage with these traumas through the “scar-literature” movement, the effort was quickly choked off: Deng Xiaoping’s 1983 campaign to “eliminate spiritual pollution” and his 1987 drive to “oppose bourgeois liberalization” shut the brief window of candor.

Gaokao prompts may have shifted from top-down paeans to everyday narratives, but they still bolt students inside a cage of “positive energy”(正能量). Violence, poverty, corruption, oppression, systemic injustice—all remain off-limits. Major historical events may be referenced only through official verdicts; any interpretation outside the sanctioned line is marked “politically erroneous.” Behind the choreographed performance of the Gaokao lies a system that rewards obedience masked as eloquence, and filters out any hint of subversion. In such an ecosystem, the humanities no longer ask students to question—but to comply, gracefully.

This careful orchestration of topics reveals a deeper truth: the Gaokao is not merely an educational tool, but a critical mechanism in the architecture of political power.

Education is always fashioned by the very institutions it serves. Authoritarian or democratic, every regime builds classrooms into its architecture of power, inheriting the rules and constraints laid down by human design and historical sediment. By rehearsing myths, epics and heroic narrative, those classrooms cultivate in students an appreciation of science, reason, and institutional legitimacy. Schools do more than reproduce order; they manufacture the social consensus that keeps that order intact, a function often more potent than any rocket army or police force.

In constitutional democracies, curricula usually prize argument and critique. The goal of education is to train citizens to navigate a noisy marketplace of ideas, to sharpen political judgment, and—ultimately—to vote. The syllabus is a rehearsal space for the pluralism that sustains party turnover and an autonomous civil society.

Under authoritarian rule, education may speak the language of “holistic development,” yet its core assignment is far more explicit: drill the sanctioned worldview. The primary task of education is to mint loyal successors, not independent thinkers. The state fears independent thought, so it fosters an atmosphere of censorship and intimidation, while still allowing controlled doses of critique and independent reasoning to keep minds—and the system itself—from ossifying. This system does change, but its evolution is always restrained as if by an invisible hand, and unable to stride freely—much like women with bound feet in old China. The moment inquiry encroaches on the legitimacy of the system itself, dissent is hustled out of the room and the door slammed shut.

The resulting intellectual monoculture is not the product of some innate docility or cowardice before power; it thrives because ideological discipline and the political system exist in a tight, mutually reinforcing embrace. The legitimacy of one-party rule does not spring from elections or open debate; it is anchored instead in an exclusive right to tell the nation’s stories. The Party monopolizes ideology, and that ideology—articulated through carefully curated histories and literary narratives—confers on the Party an authority that enables it to flourish. Any divergence is branded a “wrong view of history,” “historical nihilism,” or “incitement to subvert state power.”

The 2025 Gaokao Chinese essay prompt gave 13 million students three poetic fragments—Lao She’s “Drum‐Song Storyteller,” Ai Qing’s “I Love This Land,” and Mu Dan’s “Praise.”

The Education Ministry’s post-exam guidance proclaimed that candidates could write “argument, narration, or lyric” on any stirring angle they wished: war-time national suffering or modern national rejuvenation, love of the motherland and its people, the quiet perseverance of ordinary folk, or the iron spine of the nation. Officially, no angle was off-limits.

However, anyone who knows those writers knows better. After the victory of the Communist party in 1949, all three writers were savaged for holding fast to their own voices and refusing to use their craft to fashion state-approved battle hymns.

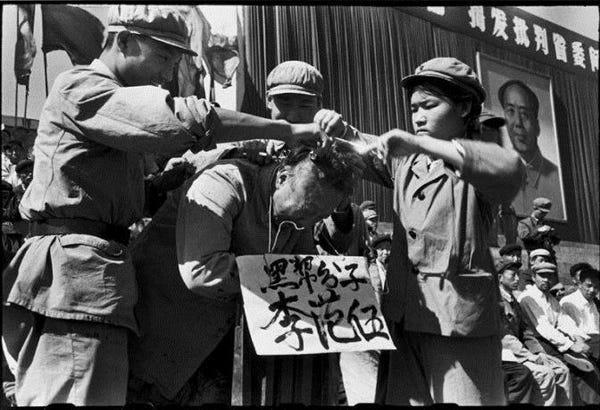

In 1966, Lao She, branded a “bourgeois-reactionary humanist,” was publicly humiliated during the Cultural Revolution—forced to kneel before a bonfire of Peking-opera costumes, beaten by Red Guards, and finally driven to drown himself in Taiping Lake. In 1968, Mu Dan was denounced by the Party as an “American spy suspect” and locked in a cowshed for “re-education.” Ai Qing, after defending the wrongly labeled “rightist” Ding Ling, was expelled from the Party in 1958 and exiled to remote northwest.

After thousands of hours of exam drills, each student absorbs a single lesson from the Gaokao: whether through amnesia, fear, or sheer blankness, they must steer clear of the bodily and psychic wreckage wrought by brutal rule and a broken judiciary, and instead chant the approved mantras of national rejuvenation and positive energy. The humanities, which ought to pursue truth, interrogate violence, and restore people to their full, fragile individuality, had been drafted into service as the regime’s mouthpiece.

The cycle is chilling: intellectuals and the humanities are forever dancing on the nib of the pen; one misstep, and they tumble from that tip into oblivion.

The Party keeps a chokehold on the nation by monopolizing the realm of ideas. The 2025 Gaokao prompt ensures China’s next generation of writers are blind to real wounds, and produce only glittering shards of praise. Selective memory—trimming sorrow, muting doubt, spotlighting emotions that can be mobilized—is the hallmark of China’s public-memory project, past, present, and future. On this grand nationalist stage, the chorus swells with anthems and battle songs.

The monsoon comes back year after year. Damp air hangs low; ceiling fans drone; students shiver in front of wheezing air-conditioners. Within ninety minutes, they must slot eight hundred characters, flush and perfect, into the ruled squares of the answer sheet. At glance each character pirouettes like a spring dancer full of promise and liberty; zoom out, and every stroke is caged in a neat little box—prisoners in a paper grid.

Beyond the exam hall a national flag climbs the pole on the rain-soaked field. In this season of perpetual drizzle, it too must halt at its assigned height—never higher, never lower.